David Chang Talks Rotting Petri Dishes, Mold, and DIY Vinegar at Harvard

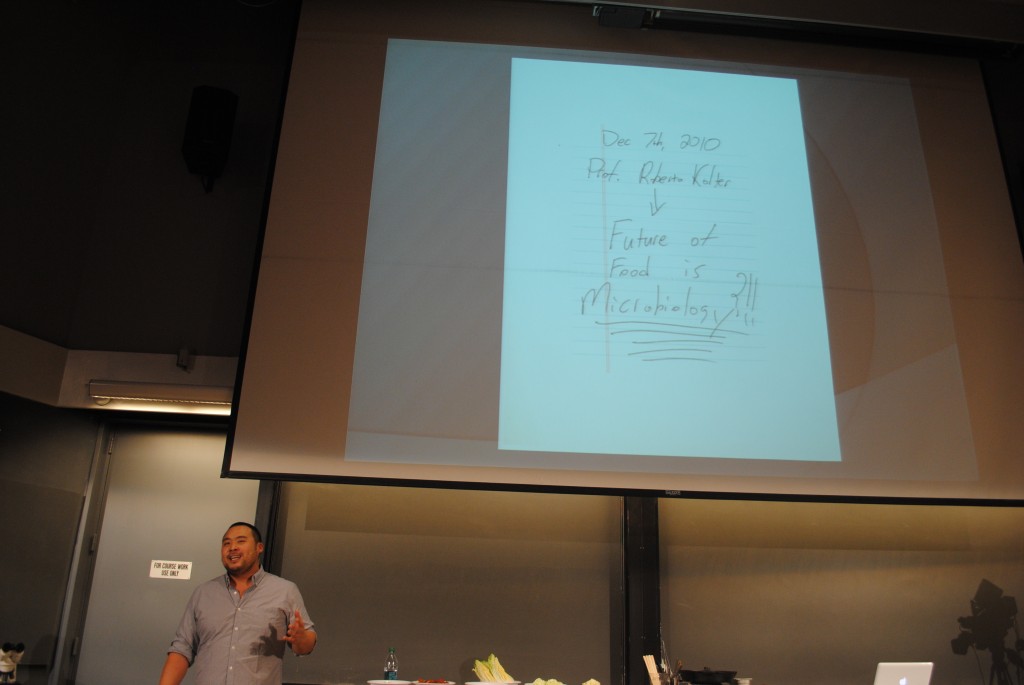

Last night, David Chang, leader of the Momofuku restaurant empire (and one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People), spoke to a packed house of food geeks, science geeks and food-science geeks as the latest high-profile chef to take part in the Harvard’s “Science and Cooking” lecture series. The topic? The role of microbiology in food.

We spoke with Chang before his talk, and he told us that microbiology is only one of many areas where Harvard has played a role in helping him improve his food. His next hurdle, he told us, is seafood-related. “We’re trying to figure out a way to open a bowl of clams at the same time [it’s] in front of a diner using hot broth,” he said. “It should work theoretically, but it’s been a disaster before.”

Chang had to leave Boston early this morning to check in on his new fine-dining restaurant, Momofuku Sei?bo, in Sydney. He told us that he hopes to be back in Boston in December to take some time off, check back in at Harvard, and visit some restaurants he’s been wanting to try, like Salts and Oleana (while he was in town, he did manage to pay a visit to Tony Maws at Craigie on Main). Ahead, the takeaway from Chang’s fascinating lecture.

Microbiology is the future of food.

The crux of the lecture was that there is an infinite number of possibilities when it comes to the relationship between the study of microbiology and food. “This is where a lot of unknown flavors are going to be,” Chang said. “These scary, Latin words have flavor when combined with food.” During the Q&A portion of the lecture, an audience member asked if he was worried about tasting different moldy food because of its poisonous potential. “There’s only one way to find out,” Chang replied. “Someone’s got to taste it.”

Vinegar is the New Wine.

Last year, Chang succeeded in creating pork katsoubushi, which is a dried and smoked bonito that is typically made with pricy fish. He fermented a pork loin in a bucket of rice, and he came up with a great alternative that was cheaper and easier to come by than traditional katsoubushi. Thrilled with the discovery, Chang thought that it would become a hot new ingredient. Turns out, no one is using it today—not even Momofuku. While great in theory, the pork katsoubushi wasn’t feasible to conduct on a larger scale because of the lack of space, storage, or time to do so ( it takes seven months to make). But Chang taken his newfound mastery of the fermenting process of bushi — as well as miso and kimchi — and moved onto a new frontier: vinegar. “Everyone wants to make wine, and I want to make vinegar,” he said.

It’s possible to create Japanese products with local ingredients.

Chang recently visited chef Rene Redzepi in Copenhagen, who famously uses only local Scandinavian ingredients at his revered restaurant Noma . By fermenting rice containing microbes native to the area, Redzepi was able to create a wholly Nordic miso paste. “It tastes Japanese, but nothing is from Japan – so what is it? These are the things that keep me up at night,” Chang said. He displayed a map that illustrated how chefs everywhere from the Amazon to Sweden to San Francisco are all trying to replicate Japanese flavors without actually importing anything from Japan, a struggle that Chang himself is trying to solve. When opening his restaurant Momofuku Sei?bo in Australia, it was difficult to get miso from Japan because of the residual effects of the tragic earthquakes. He decided the restaurant would make their own. “That was kind of a slap-your-forehead moment, we just needed a microscope,” he said.

Sometimes all you need is a rotting petri dish.

Chang and his staff in New York were testing different kinds of miso made with everything from barley to split peas to peanut butter, and they mailed a bunch of rotting petri dishes containing fermenting miso to Harvard labs for testing. At first, the samples simply turned different colors, so the researchers were underwhelmed. When they returned to the lab after the weekend, they discovered that one of the mold samples had pushed the lid off of the petri dish and was bubbling over the edge.The mold was a strain called neurospora, which is also used to make an orange mold-covered peanut patty (similar to tempeh) called oncom in West Java. “This is what gets chefs excited,” Chang said. “It’s like a spice rack, if you collide micro-organisms with food – it makes the food delicious.”

Chefs need to ask, “why?”

Chang brought up the point several times that chefs should be asking “why?” in the process of creating food. He described an instance in his younger years, when he asked a chef how plain-old cabbage turns into sauerkraut from just a little salt and humid conditions. The chef replied “it’s just like magic, it just ferments.” The answer frustrated Chang, who made the case that “chefs have to be more knowledgeable, we have to make better teachers.” He even hopes to create an online database to share what he and other chefs have learned. “I’m not really concerned with intellectual property,” he said. “Keep the information free and flowing.” — Kimya Kavehkar

Related Stories:

What You Missed at Grant Achatz’s Harvard Lecture

What You Missed at Jose Andres’ Harvard Lecture

What You Missed at Wylie Dufresne’s Harvard Lecture